Dealing with a polycrisis. By Katherine Arbuthnott, March 2025.

At our last alumni meeting a few of us discussed our distress and coping during this time of ‘polycrisis’. I think this is a theme that we need to keep talking about together right now, so we’ll do that again this month.

The challenge we have is how to keep our balance in this tsunami of horrors without withdrawing our attention to the point of denial. One thing most of us are doing is avoiding the news much more than usual, which is a good strategy for self-protection. The news is full of shocking and dangerous pronouncements, something that will automatically trigger our attention-orienting responses. We orient to anything that is unexpected or surprising, which makes it almost impossible to pay attention to anything else when we tune into the news. But in reality those announcements are just noise, often even designed to distract us from actions that autocratic world leaders are taking. But, on the other hand, we need to pay attention to events enough to identify who and what is being harmed (e.g., ecosystems, social systems, victims of war) so we can take effective action and offer support to the wounded.

The trick is to protect ourselves AND take action to change our situation. The signal-noise metaphor can be helpful with this. Research in cognitive psychology identifies 4 things we need to think about to effectively solve problems: 1) the goal, 2) our current state, 3) resources we have to work with, and 4) constraints or limitations we need to work around. For me, and for most EcoStress Sask members I suspect, the thing we want to achieve (the goal) has not changed – we want to live in a way that supports the life of the planet and all its creatures, including us. That is still the case, despite the increased intensity of the attacks against life, both environmental and human. Consuming news beyond what we need to know to serve that purpose is one of the ‘constraints’ from a problem-solving perspective. Paying attention to every pronouncement and battle keeps triggering our orienting response, preventing us from keeping our attention on our goals. So coping by reducing attention to the news is an excellent strategy. But that needs to be complemented by reaffirming our actual goal, including what we are each doing to live lives that support the flourishing of all our neighbours, human and environmental.

Despite the survival threat that tariff and ‘economic warfare’ pronouncements represent to many people who fear losing jobs, I don’t think that’s actually substantively different from the challenges of climate change. We all need to learn to live differently to ensure any kind of security.

One strategy that I’m focusing my attention on these days is ‘the gift economy’ that Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote about in her latest book, The Serviceberry. This is basically the resource-sharing strategy that provided life-insurance to our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Those of us who are lucky enough to have enough food and shelter need to share it with our neighbours because there will be other times when those neighbours will have the excess and we don’t. That’s how we evolved to live and those instincts are still in our nature. We need to stop thinking of ourselves as ‘islands’, needing to provide everything for ourselves at every moment. We are a social species and need to let ourselves remember that – none of us are alone. Sharing our fears as well as our resources CAN keep us afloat, even through times of chaos.

Topics of our original group sessions. By Katherine Arbuthnott.

I. Packing an emergency kit

II. Eco-grief

III. Emotion, coping, and regulation strategies

IV. Balancing negative and positive

V. Living with uncertainty

VI. Conversations with climate action resistors

VII. Active hope

VIII. Exercising imagination

I. Packing an Emergency Kit

The primary purpose of our groups was to discuss intense negative emotions, eco-grief, eco-anxiety, and the anger that is ignited by the global failure to make the changes we need to survive. We were also, at the beginning, strangers to each other. So before plunging into our emotional depths, I wanted to make sure that we all had emotional ‘safety valves’ to enable us to take a break from intensity when we needed. Two such lifelines are mindfulness and our personal strengths.

We started with breathing. There are many ways to encourage a state of mindfulness, but because we are always breathing, learning to focus our attention on the bodily sensations of our breath is a quick and ever-available way to move into a temporary space of calm. Most of the time, especially for those of us who live in wealthy countries, the present moment is not unpleasant. So shifting our focus to the present moment is one way to move us from fears about our future. It is not difficult to voluntarily ‘move’ our attention to a present experience, such as the feeling of air moving into and out of our nostrils. It is, however, much more difficult to keep our attention focused on unchanging stimuli so that is where mindfulness practice is useful. To provide a bridge while we strengthen our skills in holding attention to a single focus, guided meditation is useful. During the first meeting, Russell, who is a meditator, guided us to attend in a non-judgmental, non-controlling way to our breathing. At intervals, approximately when our attention would drift to something else (thoughts, random sounds, things to do, and the endless list of things that call for our mental attention), Russell would, in a quiet and soothing voice, suggest that we notice our breathing – the sensations in various parts of our face and abdomen, the sound, the effects on the rest of our bodies – bringing our attention back to the present moment and bodily experience. Like any skill, the more we practice mindful, nonjudgmental attention control, the better we get at it. We introduced this valuable ‘emergency practice’ in the first meeting, and then opened most subsequent meetings with a brief guided meditation.

The second thing we did to provide participants with a potential way to rapidly access the not-so-bad present was to invite them to identify one of their strengths. We all have things that we are good at, either by genetics or by experience, as well as things that are difficult for us. Doing something that calls on our strengths is experienced as very satisfying, usually fostering a sense of wellbeing, according to positive psychology research (e.g., Park et al., 2004). These are the actions that ‘bring us joy ‘, as Alice Bell (2022) puts it. If we have such joyful activities ‘on standby’ in our memories, we can turn to them in difficult times to provide ourselves with some respite from despair. So before inviting group members to describe their emotional pain in any depth, we had them describe the actions that evoke joy for them.[1]

With these two ‘items’ (mindful meditation & actions that bring us joy) safely stowed in our emergency backpacks, we were ready to open the floodgates to the deep emotions about our environmental disaster that we needed to discuss with others.

References

Bell, A. (2022). https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/feb/28/ipcc-climate-report-grim-hope

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, P.E.C. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 603-609.

[1] Focusing on the actions that bring us joy is also a good strategy to plan our own climate actions. Because our earthly situation is so dire and so complex, many people expect themselves to do everything, and overwhelm themselves with the burden and stress of such impossible expectations. However, if we remember that others have different strengths than us, and therefore find joy and renewal in some of the same tasks that we find extremely difficult and draining, we can more successfully contribute our strength-tasks to the earth-saving efforts, keeping ourselves healthier and more sustainably in the fight.

II. Eco-Grief

“There is a deep sadness, a quiet undercurrent of grief that does not abate. It is difficult not to feel depressed by this onrushing calamity that will – with high probability – change most of the landscapes you learned to love while wandering as a child, the woodland paths where you walk your dog, and the butterflies, frogs, wild salmon, coral reefs, bats, and bees you might see along the way. … This more-than-personal sadness is what I call the Great Grief, a feeling rising in us as if from the earth itself.” (Stoknes, 2015, p 171).

The common name for the Great Grief is eco-grief, and it is an increasing mental health challenge (Clayton, 2018; Clayton et al., 2017; Consolo et al., 2020; Gustafson et al., 2019; Marks et al., 2021). Grief is evoked by unrecoverable losses, and there are many such environmental losses – extinction of species, destruction or degradation of natural landscapes including forests, oceans, and grasslands, even loss of the predictability of our seasons and weather patterns.

We are members of a social species and we form attachments easily. As Stoknes (2015) put it, “There is a strong, strong capacity in human beings … for love”. (p 187). We form attachments to other people – our family, friends, and even celebrities – but also to lots of others, both living (pets, wild animals, trees, birds) and inanimate (toys, tools, houses, vehicles). We also form strong attachments to places, and this is an important source of the Great Grief. “There may be no bonding as strong as the attachment we form to the land while walking on children’s feet. The landscapes of your childhood are forever contained in the body’s memory.” (p 187). As for the loss of any great attachment, changes to our home landscapes evoke deep grief.

Grief is the natural response to loss and, from a psychological perspective, can be considered a healing process. Our attachments are part of ourselves, and when one is lost, it feels like an amputation, because psychically it is just that. But humans are also a remarkably adaptable species, and we’ve evolved many ways to restore ourselves when our lives are threatened – efficient immune systems that deal with infections and parasites, cell repair processes to mend skin damage, and grief to heal from broken attachments.

Our healing processes are dependable and orderly, but they take us outside the normal rhythm and functions of our life so can be disconcerting and distressing. When our immune system is fighting a virus, we feel ill, fevered, aching, and often need to take to our beds. When scabs form over skin wounds, the function of an injured limb is restricted for a time. Grief is similar, but because there is nothing to see, no fever or scab, we may be even less patient with the healing than we are for other injuries.

In considering the healing functions of grief, it can be useful to consider the stages of healing for a more visible process, such as repairing the skin after a cut. This process is complex but automatic. We don’t have to know the first thing about blood coagulation or cell renewal to heal a cut. The only thing required of us consciously is to not impede the process by activities such as picking off the scab. The process happens in stages – first we bleed to wash away impurities from the breached area and to bring a supply of white and red blood cells to the spot. The platelets then coagulate to form a hard protective covering over the cut. This natural barricade is NOT flexible or permeable like our healthy skin is and, to our eyes, it is often unsightly. But beneath this temporary covering, the work of cell repair goes on until, when the scab falls off, we have once again an unbroken layer of skin, usually with little or no scar tissue to impede its sensory and motor functions. The sensations that accompany skin healing are also orderly – usually a moment of numbness, then throbbing pain for a few minutes or hours while the scab forms, then a slow diminishing of painful sensation until, in the middle of the healing process, we often feel nothing at all except the odd ‘pull’ of the scab on surrounding skin. Before the scab falls off, we often experience a tingling, painful, or itchy sensation.

The process of healing from a broken attachment is equally complex, dependable, and automatic. As with our skin-healing process, grief requires that we do not actively impede its operation. When one of our attachments is lost, we ‘bleed’ by reviewing our thoughts and feelings about that relationship. We feel bereft at its absence from our future life, sorry that we weren’t more grateful and attentive. We remember our times together, good and bad. We then usually ‘scab over’ socially – we withdraw into mourning. We feel lack of energy and interest in others or the world. Sometimes we can barely cope with feeding and caring for ourselves. And we cry. Then, just as a scab falls off when healing is complete, we begin to pull out of this shell when we are ready. We start to take inventory of our lives and notice interests start to reawaken. We may flex our attachment function by contacting old friends, or finding places to make new ones. Slowly, we reconnect with our lives, form new attachments to people, places, and activities, and resume living. This healing process cannot be rushed any more than cut healing can.

The well-known ‘stages of grief’ models describe this process. Some models, like that of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross (1969) focus on the feelings and thoughts of grief, like the ‘numbness-pain-pulling’ stages of cut healing. One model that describes the healing itself, analogous to the bleed-scab-repair tasks of skin healing, is Bob and Mary Goulding’s (1979) grief work model. The tasks this model describes are to 1) acknowledge the facts of the loss, 2) express appreciations and resentments, 3) say good-bye, 4) mourn, and 5) say hello to today. Although grief-healing cannot be rushed, attention to some of these tasks can facilitate the process, just as cleaning a wound can hasten the bleeding stage.

1. The facts. The first step is to acknowledge the loss, which in the case of eco-grief means accepting that the land is irrevocably changed, or that a beloved species will not be returning. This stage is often delayed by ignoring the absence, as in Kubler-Ross’s (1969) denial stage. This is relatively easy to do for losses due to climate change, because the loss happens so incrementally that we may not notice it. For example, I hadn’t noticed the catastrophic reduction in flying insects until I read Michael McCarthy’s (2015) description of noticing the absence of ‘bug guts’ on windshields after a drive in the country. Once I realized that was true for me too, I also started to notice the absence of the insect-eating songbirds as well. Sometimes when we do finally notice a loss, we too quickly turn to action, especially if we are already involved in environmental work, which can distract us from addressing grief, but does not alter the reality of loss.

2. Appreciations and Resentments: As Joni Mitchell sang, ‘We don’t know what we’ve got til it’s gone’, and this is often the case with even our most beloved attachments. Once I’d noticed the scarcity of bugs and birds in my country walks, I became aware of how much I loved all that life in the fields, hopping and flying in response to my footsteps, chirping and singing accompanying my journeys. I always had plenty of company, even when I was wandering the country trails alone. Recognizing that, feeling grateful and warmed by the memories, is an aspect of expressing appreciation. We all have unnoticed and unexpressed threads that form the basis of our love for our attachments, and it is important to ‘bleed the wound’ by dwelling on these, at least briefly. And, because nothing is perfect, even the most beloved person or place, there will also likely be things that annoyed us, such as the way grasshoppers startled me, landing almost anywhere on my body and the damage they did to my uncles’ crops. It is more likely that these were noticed at the time, given our ‘negativity bias’, but expressing them is also part of ‘cleaning the wound’. The elegies written by poets and songwriters are a good example of how creative work can serve these functions, but there are lots of other ways to express our appreciations and resentments about lost attachments.

3. Good-bye: Once we have acknowledged the fact of a loss, and reviewed the meaning that attachment had in our lives, we are ready to say good-bye. There are cultural rituals for this stage when we lose an important relationship, such as funerals, vigils, and ceremonies; these can be useful ways to say good-bye to a lost love. I think of such formal rituals as analogous to scabbing over a wound. This is not the end of the healing, but rather the beginning of the repair process.

4. Mourning. This is the healing itself. Like skin renewal, it is often very painful, especially at first. We know from experience that scabs are temporary, but because our experience of grief-healing is both less visible and less familiar, many of us are not at all confident that mourning will end, and so too often attempt to ‘pick off the scab’. We scold ourselves for our feelings and plunge into activities that we’re not yet ready for. The symptoms of depression are often naturally present during mourning: Changes in sleep patterns and appetite, loss of interest, inability to experience pleasure, trouble concentrating and remembering, low energy, and immune system suppression. The work of healing from a loss happens inside us and all of these impairments make it difficult to interact with outside stimuli, which is just what we need to heal from a broken attachment. However, unlike scabs, mourning is not a steady state. Most of us experience it in waves, deep troughs of bereavement and despair, then periods of respite where we don’t feel so bad. Over time these ‘waves’ gradually trend upward toward more energy and lighter feelings, but if we don’t expect these ups and downs in emotion and function, we can feel frightened when we plunge back down from an easier peak. We may think, ‘I thought I was doing better, but I must not be. I’ll likely feel like this for the rest of my life’. Scaring ourselves like this, as well as being unnecessarily distressing, puts us at risk of metaphorically ripping off the scab, trying to force ourselves out of mourning prematurely, which often initiates a vicious cycle of depression and fear. This stage thus requires some self-protection of the process itself, just as we might take care to protect a scab from further harm.

5. Hello to today. When mourning is almost complete, our attention slowly shifts away from ourselves and our past and we start to notice the external world more. If the loss has been profound, we may notice ourselves doing an inventory of our life, assessing what we still care about. For eco-grief sufferers, this may be a time to consider what is not yet lost, what could still be saved of our land and ecosystems. This inventory is tentative at first and gradually gains momentum as the healing progresses; it is like flexing the muscles over a healing cut. We need to re-bond ourselves to the world and others. At this stage, connecting with others and even beginning new projects, is appropriate. However, in our culture we have a tendency to rush too quickly to such activities, sometimes even before the work of mourning is properly started. Interests and activities will arise spontaneously when the time is right, so there is no need to force ourselves into premature action, which is really a sign of distrust that we will heal.

As I’ve described, grief is part of our ‘biological repair kit’ and not something to fear or resist. Healing processes take time, something that we find difficult to give in our ‘just in time’ culture. But the timing is largely governed by our bodies. For example, studies of immune system suppression following a loss (e.g., Ornstein & Sobel, 1987) show that normal immune function is not restored until an average of 4 to 14 months later, depending on the importance of the lost attachment. Grief is a process that deserves the same respect and tolerance as our skin-repairing processes. Neither of these are pleasant, but they are necessary and, in the long-term, a gift to our longevity and life enjoyment.

The losses that plunge us into eco-grief are, as we know, often societally chosen rather than natural. However, as Stoknes (2015) notes, “The forces that bring us there [to the Great Grief] are more than we can personally change, so it would be unreasonable to assume that we could fend off future envelopments. There will be times when we fall into this sadness. What we can control is how we choose to get back up again. And how we find the grace to live with it. … What we can control is to experience our grief, recognize it in ourselves and others, and help each other to heal when it strikes. … Contact with the pain of the world can also open the heart to reach out to all things still living. … Maybe there is community to be found among like-hearted people, among those who also can admit they’ve been inside the Great Grief feeling the earth’s sorrow, each in their own way.”(p 173 & 176).

References

Clayton S. (2018). Mental health risk and resilience among climate scientists. Nature Climate Change 8: 260–261. www.nature.com/natureclimatechange

Consolo, A., Harper, S.L., Minor, K., Hayes, K., Williams, K.G., & Howard, C. (2020). Ecological grief and anxiety: the start of a healthy response to climate change? Lancet, 4(7), E261-E263. Doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30144-3

Goulding, M.M., & Goulding, R. (1979). Changing Lives Through Redecision Therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Gustafson, Bergquist, Leiserowitz, & Maibach. (2019). A growing majority of Americans think global warming is happening and are worried. Retrieved October 16, 2021, from http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/a-growing-majority-of-americans-think-global-warming-is-happening-and-are-worried

Kubler-Ross, E. (1969). On Death and Dying. New York: Macmillan.

Marks, E., Hickman, C., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, E.R., Mayall, E.E., Wray, B., Mellor, C., & van Susteren, L. (2021). Young people’s voices on climate anxiety, government betrayal and moral injury: A global phenomenon. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3918955 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3918955

McCarthy, M. (2015). The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and joy. London, UK: John Murray Publishers.

Ornstein, R., & Sobel, D. (1987). The Healing Brain. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Stoknes, P.E. (2015). What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming: Toward a new psychology of climate action. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

III. Emotion, Coping, and Regulation Strategies

What are emotions?

There are several theoretical models of emotion in play with emotion researchers, but the one I find most useful for practical purposes is ‘cognitive appraisal’. Appraisal theorists describe emotion as an automatic evaluation of what an event means for us. Richard Lazarus (1991) describes two stages of appraisal: whether an event is beneficial or harmful (primary appraisal) and our capacity to cope with it (secondary appraisal). The primary appraisal determines the ‘valence’ of our emotional response (i.e., positive or negative emotion). The secondary appraisal involves rapid assessment of the skills and resources we have to avoid or reduce a potential harm or to take advantage of potential opportunities (for positive emotions). This secondary appraisal determines both the exact type of emotion (e.g., fear vs anger) as well as the intensity of our emotional experience.

Appraisal theorists identify the judgments that underlie specific emotions, which I find very useful in understanding and dealing with my emotional experiences. Here is a list of the meanings behind the common emotions aroused by environmental concerns:

Sadness: irrevocable loss Happiness: progress toward or satisfaction of a goal

Fear: immediate danger Joy/Wonder: delight in the presence of something greater than our self

Anxiety: possible future danger Hope: seeing both threat & opportunity; choosing to act on the latter

Anger: wanting/demanding other to change

One of the ways this model is useful is that we can ‘work backwards’ from an emotion to consider our judgments of both the situation and our own resources. For instance, consider the emotions of sadness, fear, and anger. All three are negative emotions and thus indicate that we’ve judged a situation as harmful. But the specific emotion indicates different judgments about that harm and/or our own resources. Sadness means we’ve judged that the harm has already happened and is irreversible (i.e., something we care about is gone). Fear means that we think the harm is immanent (i.e., immediate danger). And anger means that we think the harm is caused by someone or something else and that we have some power to make them change that. It is usually useful to ‘reverse engineer’ our strong emotions in that way and reflect on our automatic judgments. Identifying that we are angry in response to an environmental harm, for instance, suggests that our best coping action might be to find others who are also working to effect the change that we want, rather than avoid, protect ourselves from (fear), or grieve (sadness) the situation.

Coping strategies

Coping strategies usually refer to dealing with negative emotions, situations that are appraised as harmful (threats). Three general categories can be distinguished based on what the strategy hopes to achieve. Solution-focused strategies aim to eliminate a threat or solve a problem, emotion-focused strategies aim to soothe or eliminate a negative emotion, and avoidance strategies divert attention away from the threat. Each is useful in different situations.

Solution-focused strategies are used when we judge our skills and resources adequate to eliminate or diminish a problem. For environmental threats these are the changes we need to reduce carbon emissions, biodiversity loss, and inequality. Climate actions are numerous and include both personal behaviour and group actions. Emotion-focused strategies are useful for times when we don’t have the resources to solve a threatening problem, such as when ‘the great grief’ strikes us. They are also useful adjuncts when our solution-focused strategies take some time to work, which is the case for most environmental problems. Self-care strategies are essential for environmental problems because eliminating these existential threats immediately is impossible for any one person or group, and sometimes the burden of these issues overcomes our ability to engage in problem-focused strategies until we replenish ourselves. Avoidance strategies are the least effective with respect to the actual threat, and so ideally would be used only sparingly. However, sometimes we can neither direct action toward the problem itself nor effectively soothe our emotional response to the problem, and in these cases avoidance can be very effective to prevent damage. A good example of the effective use of avoidance is how we use distraction with upset babies, drawing their attention to something entirely different from the thing they want when we can neither solve their immediate problem (e.g., let them run freely) nor convince them to feel differently about that (e.g., enjoy being held). Shiny objects have their place in our coping tool kit, as long as we use them sparingly.

Emotion regulation

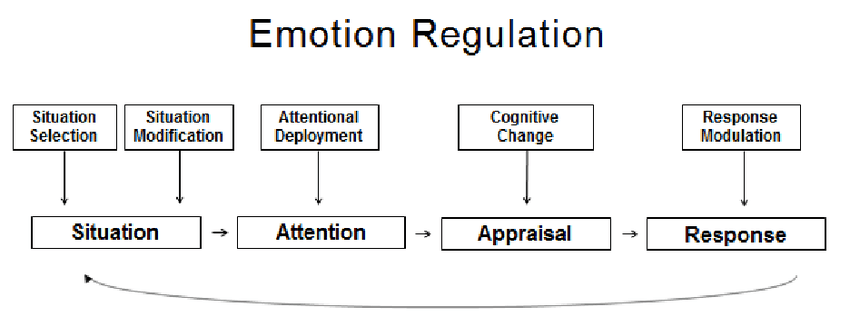

John Gross (2002) developed a comprehensive model of emotion-focused coping strategies. His model includes methods to prevent difficult emotions from arising (situation selection and modification strategies), to quickly deflect difficult emotions as they begin (cognitive strategies), and, when all else fails, to prevent harmful social consequences of unrestrained emotional displays (response modulation strategies).

Situation selection and modification. We can avoid exposing ourselves to circumstances that we know are very difficult for us. For instance, I find large noisy crowds distressing so I avoid triggering these unpleasant emotions by not attending events such as loud indoor rock concerts. We can sometimes use this strategy intermittently, avoiding certain situations when we know our coping resources are low, but not at other times. Or, if I must go to such a gathering, I can wear earplugs to reduce the noise levels that trigger my anxiety, which would be an example of situation modification.

Situation selection can also be used to foster our positive emotions and to help heal ourselves from distress. Spending time in nature is probably the best example of this strategy (except when solastalgia and grief are triggered). Nature time rapidly improves our emotional health by both increasing our experiences of positive and elevating emotions and decreasing our negative emotions (e.g., McMahan & Estes, 2015; MacKerron & Mourato, 2013; Pritchard et al., 2020), including diagnosed depression, anxiety, and chronic stress (e.g., Berman et al., 2012; Roe et al., 2013). Even having ‘pieces of nature’ such as potted plants, aquaria, or pets around us can help make a distressing situation less stressful (i.e., situation modification). Another example of situation selection is organizing ‘tech breaks’ by turning off smartphones or news channels when we need a break from them.

Cognitive strategies. Both attention focus and reappraisal strategies require practice to use, but are well worth the effort because they give us control over our emotional well-being as well as enabling effective action in those situations. There are several such strategies that enable us to direct our attention to opportunities within a difficult situation (e.g., be curious, find the silver lining), as well as to suspend judgment of others to enable productive conversations with them. Having such skills increases your coping resources, which makes the experience of overwhelming emotions less frequent because your secondary appraisal is more often ‘I can do this’ rather than ‘I can’t’.

Suppress expression. When all else fails, response modulation strategies, such as ‘biting our tongue’ or ‘showing a poker face’, can be used to protect ourselves from public displays that might haunt us. Suppressing the expression of intense emotions, however, is not a generally useful emotion regulation strategy for several reasons. First, you still feel the emotion even when you don’t express it, which means that you still need to take care of your feelings at some point. Second, holding back expression is very effortful, so you often miss what is going on while you do that. This means, for instance, that if you are holding back during an intense argument with someone, you likely won’t even hear what they are saying, and you certainly won’t remember it (Butler et al., 2003; Gross & John, 2003), which can have serious consequences for your relationships as well as for your ability to solve problems.

Knowing about these different ways to regulate our emotions can enable us to be creative in devising strategies that fit our own emotionally-challenging situations (i.e., ‘emotional intelligence’). Having a range of coping strategies can also reduce the times we make ‘I can’t do it’ secondary appraisals even when we judge a situation as potentially harmful, which can also reduce intense experiences of anxiety and stress.

References

Berman, M.G., Kross, E., Korpan, K.M., Askren, M.K., Burson, A., Deldin, P.J., Kaplan, S., Sherdell, L., Gotlib, I.H., & Jonides, J. (2012). Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140, 300-305. Doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.012

Butler, E.A., Egloff, B., Wilhelm, F.H., Smith, N.C., Erikson, E.A., & Gross, J.J. (2003). The social consequences of expressive suppression. Emotion, 3, 48-67.

Gross, J.J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39, 281-291, doi: 10.1017.S0048577201393198

Gross, J.J., & John, O.P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348-362. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Lazarus, R.S. (1991). Emotion and Adaptation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MacKerron, G., & Mourato, S. (2013). Happiness is greater in natural environments. Global Environmental Change, 23, 992-1000. Doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.01.010

McMahan, E.A., & Estes, D. (2015). The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10, 507-519. Doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.994224

Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., & McEwan, K. (2020). The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 1145-1167. Doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6

Roe, J.J., Ward Thompson, C., Aspinal, P.A., Brewer, M.J., Duff, E.I., Miller, D., Mitchell, R., & Clow, A. (2013a). Green space and stress: Evidence from cortisol measures in deprived urban communities. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 10, 4086-4103. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph10094086

IV. Balancing Negative and Positive

Psychological researchers who study emotion suggest that people who regularly experience more positive than negative emotions are healthier in many ways, ‘flourishing’ rather than ‘languishing’ in their lives. This is known as the ‘positivity bias’ (Barber et al., 2010), and research indicates that the best balance is approximately three times as many positive as negative emotional experiences (Faulk et al., 2012; Frederickson & Losada, 2005).

Although people are highly motivated to ‘repair’ negative emotions (Baumeister et al., 2001), our automatic attention processes make maintaining such a balance of positive to negative difficult. We have a ‘negativity bias’, which means that our attention is drawn to potentially harmful events much more easily than to potential opportunities. Most psychologists attribute this to our evolution: Those who quickly noticed dangers such as human-eating predators were more likely to survive (thus becoming ancestors) than those who quickly noticed opportunities such as tasty fruit or an attractive stranger. Fruit and potential friends can wait, evading poisonous snakes cannot. Even our judgment biases, such as availability heuristic and loss aversion, tilt us toward the negative.

As a result, noticing positive stimuli and events, never mind thrice as often as threats, requires both effort and practice. We can help ourselves by developing habits that cue us to look for the positive. For example, when I practiced as a psychotherapist, clients could tell me in great detail about the things that were going wrong in their lives, so I learned to ask them to also consider what they wanted more of in their lives. That enabled us to organize our work together around what they wanted more of, as well as what they wanted less of.

I learned another useful strategy to turn my attention to positive events from my son, who is a fantasy writer. When he teaches workshops to aspiring young writers, he starts by asking them what they want more of in the world. That focuses them on the things they enjoy and value, so that question works to increase anyone’s ‘positivity ratio’. For those of us concerned about our growing environmental crises, that question is also a good prompt to help us start to image possible futures that are sustainable, because our usual ‘like the present only more’ future ideas lead us to very difficult lives, if not outright extinction.

Please note that we need both negative and positive emotions in our lives. Negative emotions, as the evolution hypothesis emphasizes, help us to survive by alerting us to threats and risks. Careful attention to such threats helps us to understand complex situations, including the factors in our own behaviours that are fueling climate change and biodiversity loss. We need to feel angry, scared, and sad about this to enable us to direct our actions most usefully. But we also need positive emotions, which alert us to possibilities for growth and development in our lives. Balance is the goal, not eternal optimism. Training ourselves to ‘think only positive thoughts’, distracting ourselves from negative events, also harms our wellbeing.

Developing skills of emotional balance is analogous to learning how to balance our bodies. To prevent falls, balance training has become popular in fitness programs for the elderly. In such training, coaches emphasize that developing the muscles and motor skills to maintain balance requires us to ‘wobble’ during training. Exercises such as standing on one leg, walking over uneven ground, or walking along a fence or tightrope challenge our usual balance, making our nerves and muscles more agile to keep us upright. The same is true, metaphorically, of emotional balance. We need to challenge ourselves with periods of depression, anxiety, and frustration in order to learn strategies to ‘right ourselves’.

References

Barber, L.K., Bagsby, P.G., & Munz, D.C. (2010). Affect regulation strategies for promoting (or preventing) flourishing emotional health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 663-666. Doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.06.002

Baumeister, R.F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenaur, C., & Vohs, K.D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323-370. Doi: 10.1037//1089-2680.5.4.323

Faulk, K.E., Gloria, C.T., & Steinhardt, M.A. (2012). Coping profiles characterize individual flourishing, languishing, and depression. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 2012 ,1-13. Doi: 10.1080/01615806.2012.708736

Frederickson, B.L., & Losada, M.F. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist, 60(7), 678-686. Doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678

V. Living with Uncertainty

Uncertainty is described as being unable to interpret the present and/or predict the future. By this description, there is no doubt that we have entered an age of uncertainty. Our usual daily lives have been profoundly disrupted by climate change and all the things it causes including extreme weather events, pandemics, and global conflicts. As we have seen during the pandemic, living through such times greatly increases the incidence of mental ill health, such as depression, anxiety, and addictions (e.g., Buheji et al., 2020). So how do we maintain our emotional balance with these frequent and unpredictable changes?

Research on how to remain healthy during times of uncertainty, some conducted during the early stages of the pandemic, indicates that people who resist falling into ill-being most often have skills and habits of resilience (Buheji et al., 2020). These skills can be described as commitment to growth, flexible imagination, and curiosity.

Some of us are fortunate to have a head start in developing these skills through genetics or childhood experiences. Genetically, our brains and endocrine systems can be slightly more sensitive to rewards and opportunities or to punishments and threats. Babies who are more sensitive to rewards, which Jonathan Haidt (2006) calls ‘winning the cortical lottery’, show an ‘easy temperament’. The influential adults in a child’s life can also plant the seeds of these skills by drawing the child’s attention to pleasant possibilities in their environments, encouraging their joyful and imaginative play, and by teaching them how to regulate their emotions and to ‘play nicely with others’. But even those of us who don’t have such childhood foundations can acquire and strengthen the skills of resilience.

Commitment to growth. This habit of resilience describes the fundamental energizing role of our motivational focus. At its most basic, all living creatures have two motives, approach and avoidance (Elliot, 2006). We avoid threats to our survival and wellbeing, and we approach things that can enhance our growth. Avoiding danger and embracing life-giving possibilities are both essential to a good life and, in most circumstances, the possibilities of both are present. Except in situations of extreme danger, our ability to notice the growth possibilities and frequently choose those as the focus of our actions defines our health and development. With respect to resilience, motivation researchers have examined how people respond to failure, and find that those with a ‘growth mindset’ are much more likely to recover, tally what they can learn from the failure experience, and improve (e.g., Dweck & Legget, 1988). Those with stronger ‘avoid risks’ motives, are much more likely to choose to abandon the goal after a failure experience, so as not to experience any further losses. This can, ironically, make them much more vulnerable to life circumstances, including uncertainty. As a specific example, in a school context, a growth goal would be to learn as much as possible (a mastery goal), whereas a student with a goal to avoid dangers would focus on passing the class (a performance goal). Studies in these contexts indicate that students with mastery goals have much higher levels of achievement than those with performance goals, primarily because they are more resilient in the face of failure (Dweck & Leggett, 1988).

Flexible imagination. In any situation we make immediate assessments of meaning, the most basic being whether the situation is harmful or beneficial to us. We experience this as emotion, negative when we assess something is harmful and positive when we assess it as potentially beneficial. This, of course, underlies our automatic approach/avoidance mechanism, and happens very rapidly and unconsciously. But research in emotion regulation indicates that we can, with practice, alter our initial assessment of harm or benefit by expanding our imagination. This is known as reappraisal or reframing, and is found to be one of the most successful and beneficial strategies for regulating our emotions (e.g., Gross & John, 2003). The imagination expansion part is to consider, especially after an initial judgment of harm or danger, what else could this be about? We effectively put a hold on our initial judgment to consider other possibilities, especially potential benign or even positive options. For example, a farmer who notices someone hunting on their lands without permission may automatically appraise that as harmful, assuming the hunter is trying to steal from them. But if she asks herself something like ‘what else could this be about?’ to cue a reappraisal, they might think that perhaps the hunter is an Indigenous person pursuing a traditional practice on lands they love, which would lead to a very different emotional response. Interestingly, this rejudgment process can be seen operating in our brains – an initial activation of the amygdala (indicating stress and other negative emotions) can be muted in a fraction of a second by activation in our prefrontal cortex (planning) (Buhle et al., 2014; Ochsner et al., 2002). This imagination expansion gives us time to choose, to approach opportunities rather than immediately retreating, or to wait to see whether such opportunities evolve. In uncertain circumstances, where we can’t effectively predict the future, giving ourselves time before retreating into fight, flight, or freezing makes us much less vulnerable to mental ill-health. My example indicates one type of reappraisal, considering another person’s perspective (Webb et al., 2012). There are several other ways for us to engage in reappraisal such as looking for the humour (Samson & Gross, 2012) or silver lining (Shiota & Levenson, 2012) in a situation. Imagination is, of course, also necessary to devise alternative future paths in changed circumstances.

Curiosity. Curiosity, a characteristic that is evident in all young children, is the spark that activates both growth and imagination in any specific situation. Curiosity itself, the hunger to understand what is going on and how that works, is an expression of growth motivation (Zurn & Bassett, 2022). The ability to stretch one’s mind to new things that were previously unknown, weaving the new information into the web of existing knowledge, requires imagination. Thus, remaining open to experiencing curiosity past childhood, resisting the temptation of believing that one already knows everything important, can stand us in excellent stead during times of uncertainty.

Attention. Although it is not a resiliency skill itself, the ability to direct our attention is essential to the exercise of resiliency. The use of resilience skills, such as considering what can be learned from a failure or reappraising the meaning of an event, are always effortful even for those with the benefits of genetics and childhood teachings. Our thinking runs along two tracks, as described by Daniel Kahneman (2011) and other cognitive scientists. The foundational track, the one that is always ‘on’, known as System 1, is fast, automatic, and effortless so it best guides the multiple decisions of our daily lives, such as what to have for breakfast. System 2 is active much less frequently and is slow, difficult, and effortful, so requires our deliberate choice to use. System 1 has been described as “a machine for jumping to conclusions” and when complex issues confront us, as they do frequently in uncertain times, it is very skilled at tempting us by substituting a simple question for the complex one we face. For instance, when we hear an idea for addressing a ‘wicked problem’[1] such as how to mitigate climate change, it is much easier to decide whether the speaker is ‘a friend or an enemy’, and then agree or disagree with them entirely on that basis. This is why competition (i.e., ‘the sports model’) is so popular in everything from politics to global affairs. It is much more difficult to actually consider diverse opinions with understanding and empathy before choosing an action. Choosing to use System 2 in such situations requires a couple of things – time and attention. Really listening to others takes both. Engaging in conversation and problem-solving with others who have different perspectives and experiences than we do is much more difficult but, as in most cases of diversity, also more likely to result in effective and sustainable decisions.

So how can we equip ourselves to live with uncertainty, which often makes our System 1 strategies ineffective? The failures of our familiar and comfortable routines and choices can, as many experienced during the pandemic or in response to weather emergencies such as the non-stop crises in BC in the summer of 2021, easily lead to severe levels of anxiety and depression (e.g., Rettie & Daniels, 2020). How can we remain healthy in the face of frequently experiencing the ground of our lives shifting from under us? In particular, how can we keep our balance, staying rooted in ourselves while flexibly changing our actions in response to ever-changing conditions?

Useful practices. There are several practices that help us to develop and strengthen our resiliency skills. Meditation practices strengthen our ability to direct our attention when we need to. Practices such as journaling or gratitude rituals are excellent ways to practice reappraisal, find the growth motive in difficult situations, and exercise our imagination.

It is also helpful to have a few ‘reminder mottos’ on hand to help us bring these skills out when we need them. Mottos such as ‘just be curious’, ‘look for the silver lining’, and ‘count my blessings’ can all be useful in tough moments when our balance wobbles.

References

Buheji, M., Ahmed, D., & Jahrami, H. (2020). Living uncertainty in the new normal. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 10(2), 21-31. Doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20201002.01

Buhle, J.T., Silvers, J.A., Wagner, T.D., Lopez, R., Onyemekwu, C., Kober, H., et al. (2014) Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: A meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cerebral Cortex, 24(11), 2981-2990.

Dweck, C.S., & Leggett E.L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256-273. Doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Elliot, A.J. (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 111-116. Doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9028-7

Grint, K. (2008). Wicked problems and clumsy solutions: The role of leadership. Clinical Leader, 1, 11-25.

Gross, J.J., & John, O.P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348-362. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Haidt, J. (2006). The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding modern truth in ancient wisdom. New York: Basic Books.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow. Macmillan.

Ochsner, K.N., Bunge, S.A., Gross, J.J., & Gabrieli, J.D. (2002). Rethinking feelings: An fMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14(8), 1215-1229.

Rettie, H., & Daniels, J. (2020, August3). Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, online first publication. Doi: 10.1037/amp0000710

Samson, A.C., & Gross, J.J. (2012). Humour as emotion regulation: The differential consequences of negative versus positive humour. Cognition and Emotion, 26(2), 375-384.

Shiota, M.N., & Levinson, R.W. (2012). Turn down the volume or change the channel? Emotional effects of detached versus positive reappraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(3), 416-429. Doi: 10.1037/a0029208

Waddock, S. (2013). The wicked problems of global sustainability need wicked (good) leaders and wicked (good) collaborative solutions. Journal of Management for Global Sustainability, 1(1), 91-111.

Webb, T.L., Miles, E., & Sheeran, P. (2012). Dealing with feeling: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 138(4), 775-808.

Zurn, P., & Bassett, D.S. (2022). Curious minds: the power of connection. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[1] A wicked problem is one that involves many interdependent parts that need to be carefully balanced (e.g., Grint, 2008; Waddock, 2013). All of our existential problems, climate change, biodiversity loss, inequality, are of the wicked kind.

VI. Conversations with Climate Action Resistors

One of the most important climate actions, according to many climate scientists, is to engage in conversations with people who resist the changes we need to mitigate climate change and its related issues. Such conversations are vital for several reasons. It seems clear that our ‘leaders’, both political and corporate, will not act without considerable public pressure, so shifting social norms is one of the best ways to get the kinds of institutional and infrastructure changes that we need. Encouragingly, research indicates that we do not need to change the minds of the majority of the public to trigger such a norm shift – 25% seems to do it (Centola et al., 2018) – which makes every such conversation important. Having conversations with people who don’t understand or care about the rapid degradation of Earth’s life support systems is a tremendous contribution to climate action.

However, in our current situation of extreme polarization around this topic, how to have such conversations is not at all obvious. Given that, I think our best strategy is to put our ideas, in all their confusion, on the table, and see if we can work our way to some clarity. In that spirit, I have a few ‘pieces’ that might be useful to our discussions of this issue.

Preliminary Considerations

Having such conversations will not fit with everyone’s strengths. As we’ve discussed, no one can do everything that is needed, no matter how urgent each change is. There are just too many tasks that need to be done to mitigate and adapt to climate change and its intertwined existential problems for any one person to do. We need to work together, and the best way to do that is for each of us to do the tasks that best fit our strengths, the tasks that, as Alice Bell said, give us joy. Doing joy-giving tasks feeds our energy and wellbeing, rather than depleting it. If challenging conversations are not in your list of strengths, leave this to others who have those gifts while you tackle other things.

Preparing and Sustaining Yourself

It is important to acknowledge how hard such conversations are, even for people with conversational strengths. For one thing, they go against our social instincts to avoid conflict. Successfully navigating conversations with people who have very different beliefs and values than we do is, in a way, like learning to become a goalie. Our reflex when a hard object flies toward us is to get out of the way, but goalies must do the opposite – put themselves directly in its path. It is always hard to overcome our automatic impulses, but this is what is necessary to engage in these difficult conversations effectively. Another reason this may be hard is that some of the people we need to talk with have been the sources of our own distress by deliberately acting in ways to increase carbon emissions, or working to eliminate things that we desperately need such as wetlands and public conservation programs. For these reasons, as much as possible it is best to enter such conversations when we are feeling well, and not when we are tired, stressed, or otherwise not at our best.

When you are about to initiate or enter a conversation with a climate change resistor, there are a few things you can remind yourself of that might help you to keep your balance. First, you might start by assuming that everyone is doing the best they can, rather than presuming nefarious motives. The latter will set you up to be defensive and argumentative, which is never the most persuasive strategy. When I assume that my conversation partner is doing their best, even when I don’t like their behaviour or attitude, it is easier for me to ‘just be curious’ – to wonder how they came to their conclusions, what they are seeing and/or know that I don’t.[1] Starting with an assumption of benign motives and the intention to follow my curiosity, keeps me in the ‘zone of respect’, which is a much better foundation for useful conversations than anger, fear, or suspicion. When I start to feel uncomfortable in the face of significantly different perspectives than I hold, I also find it useful to remind myself how valuable diversity is, even when it is less comfortable than ‘monocultures’ (i.e., conversations with like-minded people).

When having difficult conversations, it is important to anchor ourselves in kindness, both to our self and to our conversational partners. Given the difficulties of these conversations, it is vital to monitor ourselves carefully throughout the conversation. If we start to feel hurt or upset by what others are saying, or find ourselves tempted to say something that might be hurtful or disrespectful to the other, we should stop the conversation. To be effective, these conversations require mutual trust, which is hard to build and easy to damage, so ending conversations before that happens means that we can continue another day.

Useful Information

Ineffective strategies. We have clear evidence that neither confrontation nor information work to change the opinions of climate action resistors. “If you want change to happen, hard confrontation is usually not productive. Coaches and psychotherapists know this. You don’t debate your client in the hope that you – the coach – win and they lose. The more you try to force change onto someone, the tougher the resistance.” (Stoknes, 2015, p. xiv). And clear descriptions of the evidence of climate change or biodiversity loss have done little to change the minds and behaviours of resistors over the past few decades. One effective strategy, though, is conversation: “Change can happen through dialogue, but what is needed first is curiosity, empathy, and focus on finding some common ground.” (Stoknes, 2015, p. xiv).

Trust. Trust can be described as believing that the other person cares about your interests (Lindenberg, 2000). Trust between people and groups builds slowly over time, based especially on experiences of moments when the other could exploit you, but doesn’t. Research indicates that trust first begins when one person takes a ‘leap of faith’ by trusting someone they have no information about. This is followed, most of the time, by the other responding by being worthy of that trust, cooperating rather than exploiting the first actor, and a ‘virtuous cycle’ of trust and trustworthiness develops (Ferrin et al., 2008). This is consistent with evidence that cooperation is at the base of human nature (e.g., Bregman, 2019; Raihani, 2021). Sadly, however, even well-established trust can be destroyed with a single counterexample. This is why we need to be so careful to maintain respect and kindness in our difficult conversations.

Cooperation. An emerging cross-disciplinary literature indicates that the prominent view of human nature as essentially selfish and competitive is mistaken. “Cooperation… is sewn into the fabric of our lives, from the most mundane of activities, like a morning commute, to our most tremendous achievements, such as sending rockets into space. Cooperation is our species’ superpower, the reason that humans managed not just to survive but to thrive in almost every habitat on Earth.” (Raihani, 2021, p 2). “There is a persistent myth that by their very nature humans are selfish, aggressive, and quick to panic. It’s what Dutch biologist Frans de Waal likes to call veneer theory: the notion that civilisation is nothing more than a thin veneer that will crack at the merest provocation. In actuality, the opposite is true. It’s when crisis hits – when the bombs fall or the floodwaters rise – that we humans become our best selves.” (Bregman, 2019, p 4). This is, Bregman says, “a radical idea … that’s legitimised by virtually every branch of science. One that’s corroborated by evolution and confirmed by everyday life. An idea so intrinsic to human nature that it goes unnoticed and gets overlooked. … That most people, deep down, are pretty decent.” (Bregman, 2019, p 2).

But, given evidence about the way that trust works, eliciting the behaviour that we expect from each other (Ferrin et al., 2008), holding the view of human nature as essentially selfish is very harmful. “If we believe most people can’t be trusted, that’s how we’ll treat each other, to everyone’s detriment. Few ideas have as much power to shape the world as our view of other people. Because ultimately, you get what you expect to get. If we want to tackle the greatest challenges of our times – from the climate crisis to our growing distrust of each other – then I think the place we need to start is our view of human nature.” (Bregman, 2019, p 9).

It should, however, be noted that the people who are most likely to conform to the model of human nature as selfish and competitive are those who have attained high status and power. For some reason, the brains of ‘alpha humans’ change in ways that make them much less likely to be empathetic or take the perspective of other people (e.g ., Galinsky et al., 2006).

Motivating values. There is evidence that environmentalists and climate action resistors have different goals in controversial situations, which means that their ideas about what ‘a good person’ would do are not the same. For example, Pennycook et al. (2020) asked people to describe what they should do when they encountered information that was inconsistent with one of their current beliefs. They found that people who identified themselves as liberals gave priority to belief accuracy whereas conservatives valued consistency and tradition most highly. For controversial issues such as climate change, when beliefs and evidence are incompatible, liberals think the proper course is to alter their beliefs to accommodate the new evidence (i.e., the scientific method), whereas conservatives think maintaining loyalty to their beliefs (i.e., faithfulness) to be most proper. Both of these are ‘motivated reasoning’ in that the choices reflect strongly-held goals – ‘accuracy’ for liberals and ‘stability’ for conservatives. Neither of these is a ‘bad goal’ because we need both a survivable planet (supported by accurate mental models) and social stability (supported by cultural traditions). These differences should be kept in mind because we are unlikely to be successful in encouraging others to consider changing their conclusions by presenting arguments that match our own goals while ignoring theirs.

References

Bregman, Rutger. (2019). Humankind: A hopeful history. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Centola, D., Becker, J., Brackbill, D., & Baroncelli, A. (2018). Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention. Science, 360(6393), 116-119. Doi: 10.1126/science.aas8827

Ferrin, D. L., Bligh, M. C., & Kohles, J. C. (2008). It takes two to tango: An interdependence analysis of the spiraling of perceived trustworthiness and cooperation in interpersonal and intergroup relationships. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 107, 161–178. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.02.012

Galinsky, A.D., Magee, J.C., Inesi, M.E., & Gruenfeld, D.H. (2006). Power and perspectives not taken. Psychological Science, 17(12), 1068-1074.

Lindenberg, S. (2000).It takes both trust and lack of distrust: The workings of cooperation and relational signaling in contractual relationships. Journal of Management and Governance, 4, 11-33.

Pennycook, G., Cheyne, J.A., Koehler, D.J., & Fugelsang, J.A. (2020). On the belief that beliefs should change according to evidence: Implications for conspiratorial, moral, paranormal, political, religious, and science beliefs. Judgment and Decision Making, 15(4), 476-498.

Raihani, Nichola. (2021). The Social Instinct: How cooperation shaped the world. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Stoknes, P.E. (2015). What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming: Toward a new psychology of climate action. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Zurn, P., & Bassett, D.S. (2022). Curious Minds: the power of connection. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[1] The new science of curiosity suggests that curiosity is about connection – between what you know and what you don’t know and between people who know different things (e.g., Zurn & Bassett, 2022). There’s humility in that but also wonder and delight.

VII. Active Hope

As our ever-more desperate climate and environmental scientists are telling us, we are at a crucial decision point for the planet. Anyone who has been involved in environmental work for any time knows that we, collectively, have been ignoring these warnings for decades. We procrastinate, failing to act on strategies to reduce carbon emissions and biodiversity loss or even to protect ourselves from the damage caused by these crises. Each year we continue to procrastinate reduces our ‘degrees of freedom’ to act effectively. Anyone who is paying attention to the climate crisis is, sensibly, regularly flooded with fear, anxiety, and sadness. We face so many complex existential threats and we have already lost so much. How, in the face of our intense fear, sadness, and anger, combined with the many times our actions have failed, can we maintain the motivation to continue working to mitigate and adapt to the climate crises? How do we maintain hope for the future? And what is hope anyway?

Hope is a topic that has been pondered by many different writers, from many different traditions, over the centuries. One school of thought is that hope is an emotion, one of the many that we have evolved and culturally sculpted. Some of our emotions are about the past: We feel sad when something we cared about is lost to us. Some are about the present, such as feeling angry when someone has insulted us or prevented us from getting what we want. But many of our feelings associated with climate stress, including both fear and hope, are about the future. The future is always uncertain because it hasn’t yet happened. We feel fear when we focus on the possible negative things that this uncertainty might bring, and hope when we focus on possible good outcomes. Both good and bad possibilities are contained in uncertain circumstances, and we can pay attention to either or both of these.[1] We are more likely to choose hope rather than fear when we remember that, because the future is uncertain, it is open to imagination and influence. As Rebecca Solnit puts it “we don’t know what is going to happen, or how, or when, and that very uncertainty is the space of hope” (Solnit, 2016, p xxiii).

Simply paying attention to hope in the face of uncertainty is better for our mental health, but what we do with that hope also makes a great deal of difference for how the future turns out. Exercising our imaginations to see the possibilities of a better future can shift our moods from negative to positive but influencing that future requires acting on our imagined possibilities. That is active hope, choosing our present actions to find a way toward our imagined better future. Optimistically assuming that the future will be fine even if we don’t do anything (i.e., passive hope) doesn’t alter climate change, as decades of inaction have illustrated. While it is true that nature is very resilient and can help reduce carbon emissions and other problems, nature’s abundant resilience is powerless if we continue to destroy and degrade so many natural landscapes. Mottos like ‘tomorrow will be a better day’ or Desiderata’s ‘the universe is unfolding as it should’ won’t help us to survive the growing environmental crises. “Hope is only a beginning; it’s not a substitute for action, only a basis for it” (Solnit, 2016, p. xviii).

Active hope, it should be emphasized, does not require blindness to our dire reality. If we are to imagine effective solutions to our problems, we need to be aware of the potential negative outcomes of our uncertain future. We need to know at least some of the catastrophic possibilities our climate scientists are outlining. But, we also need to pay attention to the possible preventive actions contained in their reports. Over the decades that we’ve been aware of the climate problems, scientists have proposed many possible strategies to reform the world to mitigate and adapt to global warming and its related threats. Even if we think that the probability for negative outcomes is greater than for positive outcomes, working to encourage those positive outcomes is the right thing to do, both for our mental health and for our world’s possibilities. When my students ask whether to bother applying for something they want but think they won’t get, such as admission to grad school or scholarships, I point out that choosing not to apply guarantees the negative outcome they fear. When they exercise active hope for their own future, they at least change the probability for a positive outcome from zero to something. The same is true for climate action.

So what helps us to stay actively hopeful? In 2013, researchers (Marlon et al., 2019) surveyed a large number of Americans who were concerned about climate change to answer that question. Participants reported their feelings of hope and doubt for the future, as well as any pro-environmental actions they were involved in. The results showed both passive and active hope: Some people reported beliefs that God, nature, or science would solve climate change, while others reported that they thought people could reduce climate change through personal or collective action. Only active hope was associated with pro-environmental actions, including support for environmental policies. Most importantly, participants reported that active hope was most strongly evoked by seeing others working to solve problems, both directly and indirectly (e.g., rising public awareness of environmental issues, changing social norms). This suggests that the actions and communications of local individuals and groups are particularly important for encouraging and maintaining active hope. In a social species such as ours, it seems that the actions of every person matter because they can counter the ever-present news of climate inaction from our business and political leaders.

Marlon et al.`s evidence indicates that all climate actions are valuable, even if only to encourage others to imagine positive future outcomes. Our news media can lead us to believe that change is instantaneous because only dramatic events are reported, but in reality most changes happen slowly and incrementally. Small changes, rather than revolutions, may actually be the most effective way to build the future we want. However, since our minds want ‘big changes’, we need to maintain our own active hope in the face of anger and disappointment that our life-damaging systems are not changing fast enough.

One way to do this, both for ourselves and to entice others into the active hope fold, is through stories. We need to collect and tell the stories of ‘small acts’, even though those acts don’t solve the whole problem. There are many examples of such small acts every time catastrophe strikes a community – stories of people rescuing neighbours from rooftops in their canoes during floods, drought-stricken farmers receiving bales of hay to feed their cattle from farmers in more fortunate regions of the country, citizens of one country sending packages of diapers and blankets to people fleeing wars in another country. None of these efforts solve the larger problems – climate change or wars – but they matter a great deal to the few who are helped. And, given the evidence that active hope is best fostered by ‘seeing’ others act, these stories also help to increase the number of people who are likely to act rather than despairing. As Patrisse Cullors, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, put it, the purpose of our actions can be to “provide hope and inspiration for collective action to build collective power to achieve collective transformation, rooted in grief and rage but pointed toward vision and dreams” (quoted in Solnit, 2016, p. xiv)

We can start to create some stories of our own ‘small acts’ by learning to savour moments of success rather than immediately moving our attention to the things yet to be accomplished. This can be hard to do, given the disparity between the things we can accomplish and our immense problems. But, as the work of Marlon et al. (2019) shows, doing so can increase the value of those small acts. For example, here’s one of my stories: About a decade ago, a small group of people who work at the University of Regina had a dream of transforming some of the water-hungry lawn on campus to food production. We called our project ‘the Edible Campus’. The first hurdle we discovered was that our campus is considered part of the city’s Wascana Park, so we needed the approval of both Wascana Authority and U of R Facilities Management. We invited people from each of these bodies to join our group so that we could collectively think about possibilities, and they turned out to be great allies. Our first success was the Green Patch Garden that we established with the student group RPIRG. Over the years this garden has involved students, international visitors, faculty, staff, and neighbourhood gardeners, and has produced many great conversations as well as tons of vegetables for volunteers and Carmichael Outreach (a local organization for disadvantaged citizens). In the years following we added a small orchard of fruit trees and berry bushes, and a beehive to pollinate both the garden and orchard. All of this happened very slowly, and with lot of effort. We still have too much lawn and use too much pesticide on campus grounds but we have a few pesticide-free areas and some lovely and delicious alternative plants. And, perhaps best of all, the garden and orchard are very visible, so they can serve as inspiration for others.

Another thing that can help us to maintain and build active hope is to consider that many components of a liveable future are already present. Once we imagine what a desirable future would look like, we can act ‘as if’ this future is already here, which allows us to see what is already possible and what needs ‘renovation’. Our very actions can invite others into sustainable ways of living, as well as directing our efforts more precisely to the things that need to change. One such possibility that inspires me at the moment is Kate Soper’s (2020) idea of an ‘alternative hedonism’, living in ways that increase our pleasure and joy, rather than acting primarily to increase wealth.[2] Soper calls attention to the pleasures that come from activities such as preparing food for those we love, gardening, and caring for children and elderly family members. Many of these activities involve hard work, but it is not hard work that exhausts and defeats us. Often such work brings us joy, followed by a healthy appetite and good sleep, which add more pleasures. What depletes us is working at tasks that have no meaning for us or, even worse, contribute to the very conditions that we want to change. Acting as if we could structure our daily lives around activities that bring us pleasure can feed our imaginations for what is possible, even in our decidedly market-driven society. It can also redirect our actions toward things we can accomplish without having someone else change (which so often fuels our anger and despair). I use ‘let’s see what we can do without money’ to remind myself of this. We obviously can’t do everything without money, but I’m often surprised by how much we can do – and by how much doing that lifts our personal and community spirits.

So in the service of active hope, let`s stretch our imaginations, follow the lead of our dreams with our actions, and tell lots of stories about our adventures. These things will make our present more fun, and might even lead to futures that look more like the ones we want for ourselves and our grandchildren.

References

Marlon, J.R., Bloodhart, B., Ballew, M.T., Rolfe-Redding, J., Roser-Renouf, C., Leiserowitz, A., & Maibach, E. (2019). How hope and doubt affect climate change mobilization. Frontiers in Communication, 4: 20. Doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00020

Solnit, R. (2016). Hope in the Dark: Untold histories, wild possibilities (third edition). Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Soper, K. (2020). Post-Growth Living: For an alternative hedonism. New York: Verso.

VIII. Exercising Imagination

In discussing hope, we realized how important an active imagination is. Active hope involves seeing both the potential negatives and positives in an uncertain future, and devising strategies to influence events in favour of the positives, both of which involve imagination. In the face of wicked problems, having an active and flexible imagination may be one of our best personal resources.

Unfortunately, our culture has increasingly created conditions that do not encourage imagination. Emphasizing safety and efficiency, our daily routines of work, school, and even recreation are built around tight time schedules and rule-based activities, which leave little room and even less respect for an active imagination. Even in childhood, traditionally the time of life devoted to ample play and imaginative activity, children are now engaged in structured and supervised activities most of the hours of their days. In this context, we need to be deliberate in building strong and flexible imaginative abilities. In particular, we need to give ourselves time to let our minds wander; we need to tolerate those times when we drift to daydreaming and boredom, let our minds be, rather than too quickly turning our attention to a task or entertainment.

Lots of programs are designed to teach us the skills of goal planning, time management, and the like. But exercises specifically designed to increase the range of our imaginative abilities are rare. Like any other skill, imagination needs to be developed and practiced. Let’s share our best ideas for how to do that. Here are a few of mine:

Read, especially fiction. The vicarious experiences we gain through novels are an extended practice of guided imagination, as we put ourselves in the characters, places, and situations described by writers, stretching our brain around things that aren’t there (which is the miracle of language, and other symbol systems). There is neuropsychological evidence that the regular practice of ‘deep reading’ changes our brains to enable more creative and integrative thought (Wolf, 2018). Read histories and anthropology, which are stories about how people used to live. Read utopias, which are possible futures others have imagined to deal with the problems they noticed (e.g., MacDonald, 2007). Read stories from other cultures, written by people who understand the world differently than we do.

Acquire expertise. Imagining creative problem solutions requires something to work with, so we can be most creative and inventive when we know a lot about an area. For example, good cooks can create delicious meals from almost any ingredients because they have a lot of knowledge about food, flavours, and cooking methods. Those who know only a few recipes have much less to work with and so are less creative. So one way to build a strong imagination is to increase the knowledge we have in memory to work with by becoming an expert in something. As Cate Blanchett (2018) put it, “There’s not going to be one magic bullet; it’s going to have to be governmental change, policy shifts, as well as consumer shifts and massive industry shifts. The way we do business with one another, the way we travel, it’s all of these things.” That means we need people with lots of different types of expertise to flex their imaginations – a great example of how our various strengths and joyful actions can work together to enable us to tackle wicked problems.